February 25

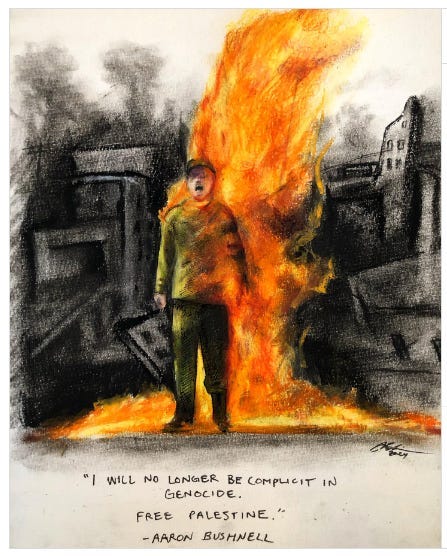

Aaron Bushnell set himself on fire to protest the United States’ complicity in Israel’s genocide of Palestinians. He was only 25.

Aaron’s death hit me especially hard. I didn’t know him personally, but he was almost my age. He too was trying to live as a person of justice in the midst of Empire. For that, he paid the ultimate price.

Maybe Aaron should have organized harder, should have worked through the white guilt instead of burning himself to death. But maybe getting America’s attention required a white man putting his life on the line. Maybe Aaron Bushnell, however misguided, was leveraging his privilege the best way his twenty-something mind knew how.

Aaron’s last Facebook post was like a cold knife in the chest:

Ideally, Aaron’s question should challenge us to think about our own actions. Will we just eat and drink and grind our lives away as genocide rages around us? Or will we refuse to allow the neoliberal order to abuse our bodies to fuel violence and genocide? Will we go beyond what Bushnell did, and commit to direct action that brings the American war machine to its knees?

But this is not an ideal world. I didn’t feel challenged; I felt shamed.

What was I doing?

I was helping the rich get richer. When I wasn’t doing that, I was wallowing in my own vices. I was too dysregulated, too isolated, too pathetic to do anything but wire a few hundred dollars to nonprofits here and there.

This reminded me of a similar question my mom would ask when I was growing up. “When you go before Jesus, He’s going to ask you, ‘What have you done for my kingdom,’” she said. “What will you tell Jesus?”

What would I tell Jesus?

What have I done for the kingdom? Would anything I’ve done ever be enough for the Kingdom? Would God understand that living under the shadow of my very evangelical mother and working the evening shift and weekends keeps me from doing very much?

The following day, my friend Elly and I prayed about this. As she was doing listening prayer for me, she got the image of green noxious gas seeping in from an iron door.

“It’s strangling my spirit,” I croaked, shrinking under the cruel voice’s tight grip.

The online Lent small group I attended later that day addressed the question from a different angle. “This hits at what you have accomplished, not who you are,” said Yulan, the small group leader. “The question should be, who are you, and who are you invited to be? That is very different from the checklist of shoulds.”

Yulan suggested that Jesus would most likely ask me a different question.

“If you are the kingdom,” they said, “then how did you nurture and love yourself in the best way possible? And how did you allow that to overflow?”

Meanwhile, I was asking a much simpler question: What needs to change so that we can be free?

March 6

Today was one of the worst days I’ve had in a long, long time.

Ever since the “green gas” vision, I started reading the Bible and praying about its contents (praying the Bible), fighting hard for my spirit to live. But even that was not enough to break the spiral of toxic thoughts swirling around in my head.

Here’s an excerpt from a journal entry I wrote after giving up on praying the Bible. In addition to the usual angst about whether college consulting is a dead end job, I was worried that my intention for Lent was not enough:

I am also very miserable whenever I think about how God sees me. It is hard for me to believe that I am doing enough for the kingdom right now. It is hard for me to believe that it is OK that I am not fasting for Lent.

It is hard for me to believe that God is not an unforgiving taskmaster. It is hard for me to believe that God is understanding. So I don’t want to pray. I don’t want to ask God for anything. I don’t want to say things that I don’t believe are true.

Not having a plan like I did last year was a double-edged sword: while I wasn’t shaming myself for not following my plan, I was shaming myself for failing to prepare a set discipline or intention for the season. Hell, I didn’t even get out of bed early enough to go to Mass properly!

It didn’t help that while the Palestinians were starving, I was overeating and didn’t know what to do about it.

I’m starting to realize that part of my experience living with autism is not knowing when enough is enough. Maybe it’s the comorbidity with hyperphagia (extreme hunger), maybe it’s the spatial difficulties. But whether it’s mixing too much paint in stagecraft class or grabbing a greater portion size than everyone else, this makes me come off as wasteful and excessive.

In one of his rare moments of lucidity, PJoe tried to teach me the difference between being filled and being full. That sounds great, except that his teaching methods were forcing me to eat an entire jar of kimchi or making me run laps around a parking lot right after dinner. Consequently, I spent the next three years spiraling into cycles of overeating and then loathing myself for “gluttony.”

By junior year of college, I was diagnosed with GERD and acid reflux. I still cannot eat blueberries without having stomach acid surging up my throat.

Long story short: if I wasn’t fasting, I was overeating. I was being undisciplined. And that made me hate myself even more.

Then Mom walked in on me shame spiraling.

“Who told you that God’s gonna ask what you did for his kingdom?” she demanded.

You did.

Anyway, she said that being a working person is enough. She also said I shouldn’t worry about Gaza and I should just be grateful that I am not there right now.

After that conversation, I wrote the following excerpt in my journal.

I still hate myself. And even though the pressure looks different, I still hate myself. I can’t even connect with God. I hate myself.

“Can’t believe you are in the workforce already your parents must be so proud of the man you are 🥲” Pastor Daniel texted me. He was my last pastor before I left my childhood church for good.

Well, I don’t feel proud of me.

It was a rough day at the office.

I opened my inbox, only to find that one of my favorite clients was…really struggling. I started cursing myself for not warning them strongly enough about taking on many classes, too many competitions, too many extra projects… I had built a strong connection with this student over the past year, and it hurt to see them hurt.

I also lost a client who I had been very excited to work with. I felt rejected, anxious, confused. I spent a whole 30 minutes writing (and agonizing over) an email to Jenny, asking for clarity on what exactly I did wrong to lose a client’s trust so fast.

I eventually forced myself to log off my work laptop.

“We’ll figure out what I did wrong tomorrow,” I told myself, sighing and making the sign of the cross.

I knew I needed to exit this shame spiral. But how?

Normally, I would drown myself in homework or digital vices (both safe and not safe for polite conversation). But my burning eyeballs told me there would be no more staring at a laptop that day.

I ran through my mental checklist of coping methods:

Running? No, running would make me ruminate even harder.

Pray? No, my Christian shame made me dread the thought of coming before the Lord.

Read? Bruh. My brain was cooked.

So I tried the only solution I could think of: Phone a Friend.

Most people call their friends to vent, but that isn’t always the best way to handle things. In The Defining Decade, pop psychologist Meg Jay warns that when we let other people’s frontal lobes do the self-soothing for us, “we don’t learn how to calm ourselves down, and this in and of itself undermines confidence.” The answer, she says, is to “answer our emotional brain with reason.”

But Meg Jay is not my therapist. Besides, I wanted to try something that I call a “distraction:” doing something else to allow my intense feelings to subside. Instead of venting about my own problems, I wanted to listen to others talk about their own lives.

The first person I called was my friend Estevan, who was climbing the learning curve of starting a part-time job at a fast-food restaurant. He ended up venting, but I appreciated his insights on how he self-regulated while figuring out his job: “You can assume that people are willing to be patient with you,” he said. “(1) they were in your situation not too long ago (2) they will probably forget that they were frustrated with you an hour later.”

The second person I called was my cousin Anne, who was climbing the learning curve of running a fast-food restaurant. Anne also ended up venting, but I appreciated her willingness to spend time with me anyway. I soon realized that this phone call was just as helpful for Anne: somehow, my riffing off her comments had reminded her of “so many things I needed to hear.”

Strangely enough, I didn’t feel burdened from holding space for others - I felt gratitude that my friends would be willing to walk me through their own stories. As I later explained to Anne, immersing myself into other people’s worlds helped me get out of my head. These fresh perspectives also activated my training with Elena Aguilar’s “Three Good Things” method, allowing me to finish my journal entry on a much more hopeful note:

I also had a ton of good meetings with clients, even if they were dealing with people misunderstanding my instructions.

I also got better at using a drill and hammer today. During stagecraft class, I drilled some really nice pilot holes and hammered in some good staples. Christian called me the hammer today. “The hammer is waiting,” he said in a deep comical voice.

I blessed two people today by holding space for them - Estevan and Cousin Anne. I wasn’t even trying to do that. I was trying to use them to distract me, and they shared their stories about how adulting is shitty.

I’ll grade this day a B: not everything went the way I wanted to, but I did some good shit today.