“Maybe that’s why I never wanted to go here.”

I was having an “aha” moment in the most random place ever: the little quad in Cypress College, between the leadership building and the student union. Occasionally, canvassers will camp out here to smooth-talk passerby into signing their petitions or joining their little cult or whatever.

Usually, I zoom past them on my skateboard. But today, I was hooked.

Maybe it was the lack of anything better to do before stagecraft class (which I dreaded). Maybe it was the interactive Post-it note activity, which challenged people to go wild with their suggestions for making the campus a better place. Maybe it was the canvasser I was talking to, who connected with me over our shared experiences of USC’s campus and urban planning buzzwords.

As we chatted, I noticed the central contradiction in many of these post-it notes. Many of them asked for more shaded areas to sit in, but I saw plenty of tables with umbrellas surrounding the campus’ giant pond. They were all empty.

This reminded me of my readings on New Urbanism, especially from Jane Jacobs. In The Death and Life of American Cities, she observes the following:

This last point, that the sight of people attracts still other people, is something that city planners and city architectural designers seem to find incomprehensible. They operate on the premise that city people seek the sight of emptiness, obvious order and quiet. Nothing could be less true. People’s love of watching activity and other people is constantly evident in cities everywhere.

The issue wasn’t the lack of shaded areas. The issue was that nobody wanted to sit by the pond. Nobody had a reason to be there, so there was nothing to do and nothing to see. No wonder everyone wanted to eat in the cafeteria or the student union!

Recalling my undergrad days, I wondered aloud why Cypress College didn’t have a “real” central hub. Why was there nothing like Tommy Trojan, an iconic meeting spot where students could gather? Why was there nothing like the canopy-shaded areas around Tutor Campus Center, where students could congregate on couches among beautiful potted plants? Why did everything look like a prison?

Then my “aha” moment came: maybe there was a reason why I never had any special attachment to the college across the street.

Sure, going to Oxford Academy gave me the expectation that I would go to some top-tier university outside of the ‘burbs. But Oxford also gave me plenty of opportunities to take dual enrollment courses, and I knew that plenty of Oxford alumni who went to Cypress have done great things. Nonetheless, I never saw myself at Cypress College, at least not until I decided to explore a career pivot to graphic design.

Maybe the real reason why I never wanted to go to Cypress College wasn’t the stigma attached to two-year junior colleges. The reason why I never wanted to go was that Cypress College felt…dead.

I’m not entirely sure that my comments went anywhere. I hope it was at least gratifying for the canvasser to have one (somewhat) nuanced suggestion. It sure was gratifying for me to have someone help me process several years of unprocessed thoughts.

Regardless, the question remains: why does Cypress College have no real central hub? To answer that, we’ll need to dive into photographs, news articles, and a whole lot of educated guesses.

The canvasser I was talking to speculated that this was because Cypress College was built in the 70s - the heat of the Vietnam War protests. The people in charge likely wanted to avoid the violence that gripped universities like Kent State and Wisconsin, she said, so decentralizing the campus was a measure taken to dissipate tensions into smaller, isolated areas.

She has a point. One protest got so heated that basketball hero Tom Lubin had to step in to de-escalate. And if this year’s Palestine protests taught us anything, college administrators are perpetually desperate to control and contain student demonstrations.

But of course, the truth is a little more complex.

Perhaps the first place to look is “Nostalgia,” an online photo gallery published by the College in 2018. Based on what I’m seeing there, I’m going to concur that Cypress’ campus planning did prioritize addressing dissent - just not through antisocial means.

One of the photograph captions shows that each academic discipline received its own building, food service area, and even branch of government. This most likely encouraged students to discuss issues in smaller, dispersed spaces, diminishing the possibility of (or need for) collective action. While the food service areas and student government branches eventually centralized into the student union and the leadership building, we can still see their legacy in the Business, Science/Engineering/Math, and Technical Education 1 buildings.

I’m also going to extrapolate that this setup was the reason why each building was named after an academic discipline, not some big-wig donor. I realized how much of an institutional asset this was in the summer of 2020, when I was in my “second-year sociology student” era and looking for anything to critique. At USC, names like “VonKleinsmid Center” and “Cromwell Field” were easy to denounce as racist. But at Cypress College, names like “Humanities” and “Fine Arts” were much harder to hate on (much less feel anything about).

But the big surprise wasn’t the localized conversations or apolitical naming conventions. The big surprise was that there was a central hub: the pond!

In the 1970s, the pond was home to “Duck Pond Races,” which brought scores of participants and onlookers until the 2000s. The pond also had a stage that often held concerts and other performances. The pond wasn’t some landscaping thing-a-ma-blob: it was the home of student life and joy.

If we’re to believe “Nostalgia,” then Cypress College’s original setup wasn’t a conspiracy to stifle free speech. There was a central hub, and the administration’s decision-making (while self-protective) appears to promote a positive student experience. The reason why Cypress College doesn’t have this hub anymore, Nostalgia suggests, is that construction happened and life moved on.

But of course, the truth is a little more complex.

Fast forward a few decades later.

It’s 2009. The piazza next to the pond gives way to the Student Center. The stage across the pond is nowhere to be found. In its place is a veterans’ memorial: a whole lot of military flags, and not a whole lot of places to sit.

And at the pond's eastern edge, the college earns its first Jefferson Muzzle.

Just outside the library, two men and three women get slapped with handcuffs and stuffed into police cars. Their offense? Handing out pamphlets and talking with people about why abortion is wrong.

Whether or not you agree with them, you probably won’t agree with then-president Michael Kassler’s response: “We have a designated free-speech area and we have asked them to be in the free-speech zone.”

Even the prosecution finds this excuse unconvincing; they convince the judge to throw out the charges. The judge goes one step further, wiping the arrests off the students’ records.

Let’s talk about this “free speech zone.” The Jefferson Center, which bestowed the muzzle, said it was “so remote from the campus center that their message would have had little impact and reached few listeners.” As a Cypress College student, I can guess where this zone would be.

Today, there’s a “free speech” board tucked away next to the humanities building. Look at the hallway where this is. It’s far away from the leadership building or the student union. And if you’re a humanities student, your classes are upstairs or in the building next door. Why would anyone come here?

Regardless of whether I’m guessing correctly, this decision to stifle tough conversations also shuts down what could have been an excellent teaching moment. If anything, this is the type of decision that leads people to dismiss Cypress College as a sociopolitical graveyard where having opinions is a liability, not an asset.

I’ll even take this one step further: this type of decision models the spirit of avoidance that is all too common among people in my generation. I find it really sad that my peers feel like they either have to attack or ignore opinions they disagree with. But where did they learn this behavior from? Educational environments that failed to encourage healthy public disagreement.

And whether or not you agree with this, we’re also seeing a whole lot of campus planning decisions that just don’t make sense. Placing the free speech board next to the humanities building could’ve made sense with the decentralized student government of the 1970s, but it makes no sense today. And placing the umbrella tables around the pond could’ve made sense with the Duck Pond Races of the 1970s, but it makes no sense today.

And it doesn’t make sense that someone who lives across the street would want nothing to do with Cypress College until he was done with undergrad.

I could’ve just ended the blog post there, but the sense of closure would’ve felt fake. Colleges are complex places run by an ever-changing, complex cast of admins. So for every questionable decision, there is always a decision that makes sense.

For the sake of complexity, I’ll end with a story that has both: the history of the O’Cadiz Sculpture.

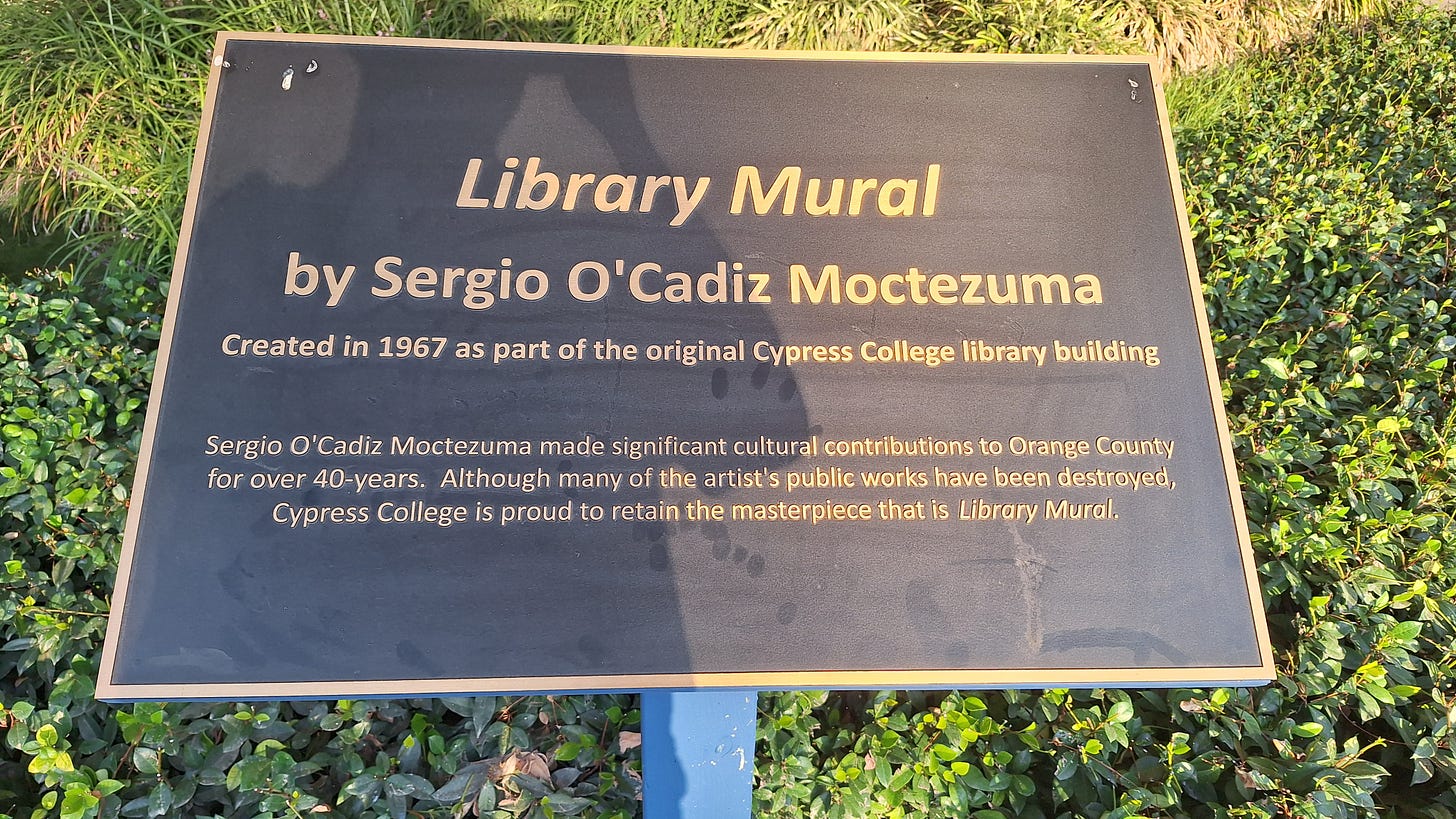

In 1967, Cypress College opened its first library building - a bare-bones, blocky building fitting the Brutalist tendencies of the college’s principal architect, William Blurock. It would have been unremarkable had it not been for a key nuance: Blurock supported the presence of art in his building designs. As a result, the library building’s west side had a mural sculpted onto it, courtesy of Sergio O’Cadiz.

O’Cadiz was also a Brutalist, but his aesthetic drew from the Mexican muralist tradition and his training at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (the “Harvard” of México). Seeing an opportunity to add something special, he went to work on a wall jutting out from the building, etching suns, roosters, and other abstract geometric patterns. The result was a mix between a rocky cliff and a Pre-Columbian carving on a grand scale: a distinctive exception to Cypress College’s grey uniformity.

This caught the eye of college president Daniel Walker, and not in a good way. His take: it was fit to “renovate the whole scrap iron business.”

To be honest, I’m with Walker on this one. But somehow, I’m still drawn to the man behind the mural.

When O’Cadiz wasn’t trying to salvage Brutalist monstrosities, he was painting murals to bring Mexican history and culture center stage. Throughout Santa Ana and all over Orange County, his artworks showcased Aztec eagles, Chicano revolutionaries, and striking workers. “My idea of America,” he told the L.A. Times, “is the right to be as Mexican as I want.”

He didn't have to do this. He was rich enough to move his family from Mexico to a home he had bought in Huntington Beach. He didn’t even consider himself a “Chicano artist,” finding the label too restricting and the movement too narrowly nationalistic. But his Mexican heritage mattered to him, and he wanted it to matter to the entire county.

For a while, the powers behind the Orange Curtain humored O’Cadiz, even showering him with media features, gallery invites, and mural contracts. But when he decided to paint police brutality on his Colonia Juarez mural in Fountain Valley, they began to push back.

The gallery invitations stopped coming. The clients stopped asking for him. The media started mocking him as “the angry Mexican artist” with “unruly hair and rumpled clothes.” As for his Colonia Juarez mural? The city pulled the funding O’Cadiz needed to seal the paint properly, allowing the mural to deteriorate into a “faded eyesore.”

In 2001, Fountain Valley bulldozed the Colonia Juarez mural. The following year, O’Cadiz passed away. Since then, city leaders county-wide have found reasons to whitewash his murals, one after the other.

But for whatever reason, the Cypress College mural has remained standing (President Walker’s objections notwithstanding). In 2016, the administration even contracted an architecture firm to clean and restore the structure. Why?

Maybe it was the determination of O’Cadiz’s daughter Pilar to make sure he received his flowers (and the upsurge of features in local media, which I pulled from profusely). Maybe it was pure convenience, the ability to feature commercial art that fit a diversity initiative.

Or maybe we can take a break from my Gen Z cynicism, and listen to Gustavo Arellano, OC journalist extraordinaire: “[Cypress College] sees a metaphor of itself in O’Cadiz: forgotten by the rest of Orange County, despite its talent, and just waiting for everyone else to love it.”

That hits a little too close for comfort.

“You’ve had good…ish experiences with campus ministry. If you’re missing college, why not go back again? You live next door to one anyway.”

It was the winter of 2023, and I was deep in a fatalistic funk. Noticing this in our conversations, my church friend Paul gave this suggestion in his soft-spoken but probing way. He succeeded at pulling me out of that funk…just not in the way that he intended.

I tried taking a stagecraft class, thinking that it was just going to be painting sets and props. One of my old mentees had taken this and gotten an A, so it couldn’t be that bad, right?

I found out the hard way that it was actually wood shop.

By the time that we had finally gotten to scene painting, people had caught on that I had no experience with power tools, and therefore no idea what I was doing. They were frustrated at me for being clueless. I was frustrated at me for being clueless.

While I found my footing somewhat with mixing paints, my lack of technical theatre background continued to hold me back. I often forgot to prime the wooden sets with slop, which wasted paint and annoyed my groupmates. I also forgot to spread out the paint with long strokes, which left paint blobs and annoyed my groupmates.

At the end of it all, we took a few photos of our miniature set. Then we kicked it into scrap wood, chucked it into the dumpster, and got our final grades. I didn’t ask for anyone’s Instagram; nobody asked for mine.

I tried using my lunch hour to attend “College Christian Fellowship,” the campus ministry that met in the same building that O’Cadiz had sculpted decades earlier. The meeting itself was okay - they read a Bible story about Jesus’ conversation with Nicodemus, asked a few scripted questions about being born again, and talked about how great their baptism experiences were.

Then one girl talked about how she wanted to show the gays that the Christians didn’t hate them - they just wanted the gays to stop being gay. Everyone nodded approvingly.

This might have been wholesome when I was eighteen. But six years of manuscript study and deconstruction later, I didn’t have the energy to deal with…this. I never came back.

Let’s be real…what was I expecting from the college ministry of a predominantly-white Southern Baptist church?

I tried attending the Media Art and Design club, one of the few that met on Mondays. The first meeting had us get into pairs and draw using each other’s prompts. The second meeting, which was about a month later, had us showcase our own artwork in front of the entire club. The next meeting was supposed to be a guest speaker from the industry, but I didn’t get to go.

Then the leaders ran out of energy to do anything other than play gartic.io.

If that sounds overly salty, then you’re not wrong. I was hoping to meet more people, but I wasn’t expecting these people to be irreconcilably different from me, whether it was vocational skills, religious convictions, or sense of purpose. I was either more or less competent than the people around me (sometimes both), and this made it hard for me to develop healthy peer relationships with these people. And that was the same problem that I had run into everywhere else.

I guess I could’ve tried harder. I could’ve tried more clubs, taken more Media Art and Design clases, even initiated hangouts with the people I did meet. But why would I bother? Fullerton College had more specialized graphic design classes than Cypress College did, so I wanted to take those classes instead. Besides, I was balancing a full-time job, a half-assed social life, and a whole-ass career pivot at the same time.

This mindset describes the vast majority of Cypress College students, and it’s the reason why the campus is known as a commuter school. It’s also the reason why I don’t have the inside scoop, much less the qualifications to write a local history of Cypress College.

The most qualified person would actually be Jon Olson, the City of Cypress’ resident historian. But I’m not sure he’d be excited to see me after I asked a few too many pointed questions in 2020. More on that in a future blog post.

So why did I even bother writing this piece?

Maybe I wanted to practice interpreting complexity with charity – a skill that I’ll need at Admission Masters, Duke, or wherever I go. Maybe I wanted to make sense of a very confusing time in my life. Maybe I just wanted to procrastinate on my Living Into Lent series, because digging into my dysfunctional social life is a little easier than digging into my experience at The Giving Farm or the ASTA anti-layoff rallies.

Or maybe I wanted to suggest a few questions for the local church to ask themselves:

How would Jesus speak to young adults who are living in transition? How can the local church include these people without talking down to them?

How would Jesus discern the spirit of an educational institution? If there is a spirit of avoidance, how can Christians model healthy disagreement…or even faithful dissent? If there is a culture of death, how can Christians model the living hope of Jesus Christ?

How would Jesus counsel educators and urban planners, especially as they make structural decisions impacting the care that students will receive for generations to come? How can the local church shape their imaginations?

But I’m hard-pressed to find a church in the area, evangelical or mainline, that addresses these questions. Then again, what can I do about it? I’m just another denizen who’s going to leave Cypress by next fall.

Until then, I’ll continue to flesh out A Denizen’s Guide to Cypress.

Do you have any observations or questions that you’d like to add? If so, comment below and we’ll chat.

As always: fight proud 📢, fight strong ✊, and fight on! 🗡️